Let’s get it right about BTS 10:90

In an attempt to eradicate abandoned housing projects, the Madani government intends to adopt, under the 13th Malaysia Plan (13MP), the concept of built-then-sell (BTS) mandatorily for all housing development.

This is to be enforced through amendments to the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act (HDAct) as announced. There is, in fact, no need to amend the HDAct as it has been in the legislation since 2007 (PU(A) 395/2007), having been implemented on Dec 1, 2007.

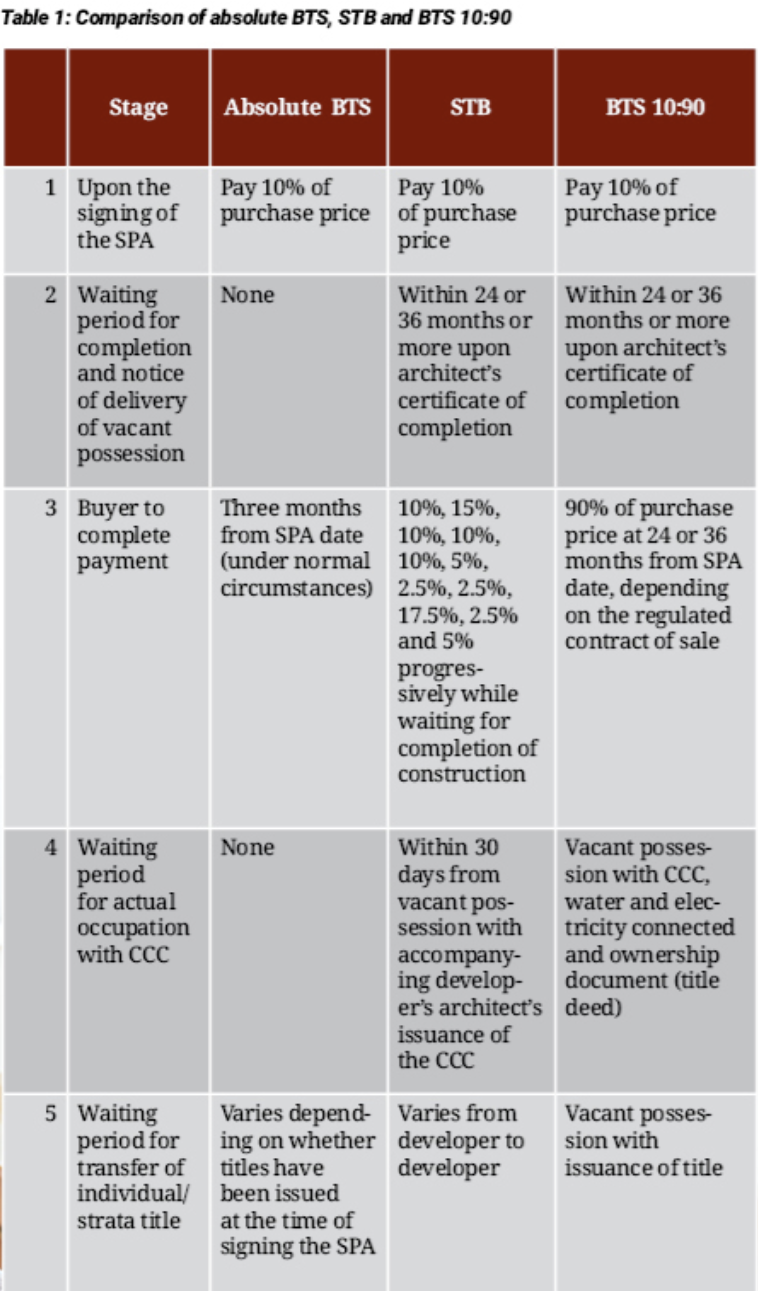

Before proceeding, we must address the confusion surrounding absolute BTS and its variant, the BTS 10:90. The fact is, there are marked differences between the two systems.

Under the absolute BTS system (or 0:100 concept), developers can only sell finished products that are ready for buyers to occupy. This is in contrast to the conventional sell-then-build (STB) system, where buyers pay 10% of the house price, followed by progressive payments as the developers build.

On the other hand, under the BTS 10:90, buyers pay 10% upon signing the sale and purchase agreement (SPA), with the balance 90% only payable upon full completion and delivery – meaning the houses have separate titles, the Certificate of Completion and Compliance (CCC), connected water and electricity and house keys.

In short, it is a hybrid between the STB and the absolute BTS.

Big hat needs big head

Under the absolute BTS (0:100 concept), financially strong housing developers will be in a better position while financially weaker developers will face difficulties, as the government claims.

However, small developers tend to develop small projects while big developers do bigger projects. As the saying goes: “One can’t possibly wear a big hat on a small head.”

From this, we can conclude that the government was referring to the BTS 10:90 version, not the absolute BTS. In Professor Nor’Aini Yusof’s 2014 book entitled Housing the Nation: Policies, Issues and Prospects, she gave a balanced view on each of the two systems but we believe that in her elucidation, she presents a more positive outlook on the BTS 10:90 concept.

Below are some highlights from her concluding paragraph in Chapter 11, page 289: “Proponents of the BTS and STB have both been very vocal in expressing their arguments and views. The government, for whom both sides are important stakeholders, needs to weigh these views carefully. It has already expressed its commitment to make BTS mandatory by 2015.

“Incentives have been introduced by the government to facilitate the BTS approach, including fast-tracking the planning approval process, waiver of deposit for the developer’s licence and an exemption for low-cost housing. But as Walczuch et al, (2007) have warned, and as past experience has shown, housing developers will undoubtedly be even more vocal and critical about BTS as we approach 2015. They will likely find excuses not to implement BTS, or at best, they will ask for more help in doing so.”

The resistance to the BTS approach is certainly not helpful to the housing industry and the country’s development. Certainly, there are direct and indirect costs incurred as developers adjust to BTS, but its adoption should be viewed positively as a means to further safeguard the interests of house buyers and perhaps further enhance or restore their trust in developers.

Closer cooperation and engagement will ultimately create a win-win situation for all stakeholders in the housing industry.

The way forward

A few publicly listed and financially strong developers with developments in prime locations have adopted the BTS 10:90 concept using Schedule I (SPA for Land and Building) and Schedule J (SPA for Stratified Buildings); hence, it is not a totally alien system. Even housing developers in Putrajaya have already adopted the BTS 10:90 model under PPA1M (1Malaysia Civil Servants Housing Projects) to offer protection for the civil servants who form the bulk of the buyers.

Housing projects that are built and marketed using the BTS 10:90 concept must use the statutory standard SPAs where the buyers pay 10% as a deposit and only pay the balance 90% upon full completion by the developer. The 10% paid to the developer is deposited into the Housing Development Project Account and the sale is locked in.

For the house buyer, it is still a purchase based on brochures and advertisements of a concept. The 10:90 concept is still a sell-first, then-build model as homes are yet to be built or completed at the time of signing the SPA.

Just like buying a motor vehicle, there is no progressive payment due to the manufacturer. On completion, the seller delivers the product and collects the balance payment.

It is actually a midway point between the present progressive payment (STB) and the complete BTS. You may call it a variant of the STB or a variant of the BTS or deferred payment basis; it matters little.

However, the key difference is that if the developer fails or abandons the project for any reason, the buyers are insulated from the developer’s business risk and possible disastrous fallout.

As can be seen from Table 1, the 10:90 payment system is still a contract to sell (through the signing of the SPA), build, then deliver. The term BTS is hence not appropriate and should not be used in its entirety when referring to the BTS 10:90 concept because the two systems encompass substantially different characteristics.

To avoid further misconceptions and confusion, perhaps we should all refer to this model as the BTS 10:90 concept rather than confusing it with the absolute BTS concept.