Undercurrents in solar wave

WITH the fifth cycle of Malaysia’s large-scale solar (LSS5) programme and its supplementary round, LSS5+, the solar industry is experiencing a fresh wave of momentum.

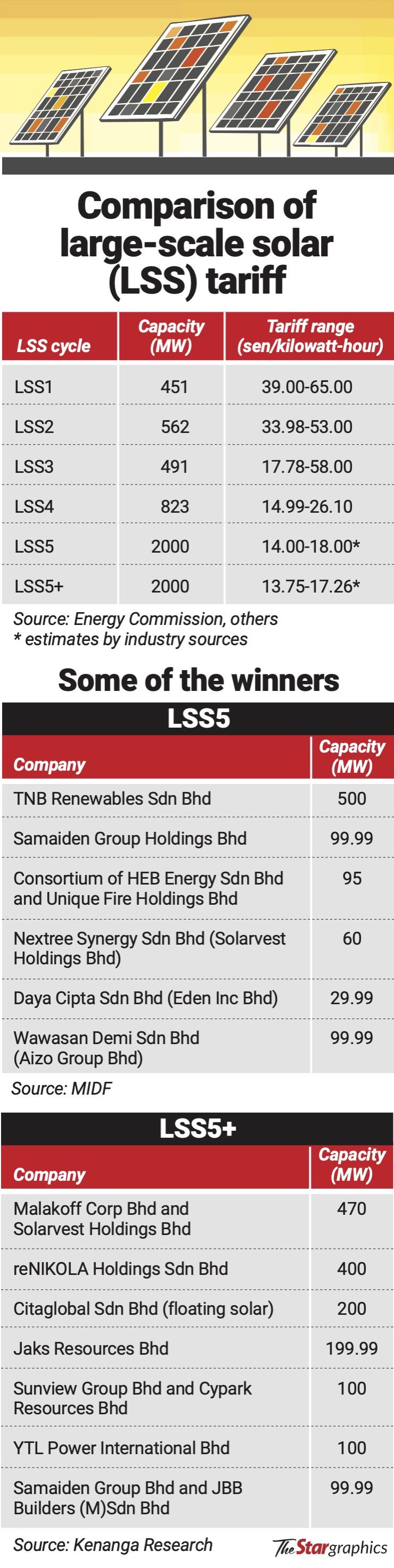

The two rounds entail concessions given to around 25 winning bidders to build out a total of four gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy (RE) capacity, almost doubling the 2.2GW rolled out under the previous four LSS cycles from 2016 to 2021.

(From all solar programmes in the country, Malaysia today has a total of 4.2GW of installed solar capacity).

The new 4GW of capacity to be built from LSS5 and 5+ will spin off RM10bil worth of engineering, procurement, construction and commissioning (EPCC) jobs, notes TA Research.

So is it boomtown for the sector?

Are we returning to the go-go days of the first generation of independent power producers (IPPs) from the 1990s, that enjoyed hefty tariffs and bumper profits for many years?

Not quite. Due to the competitive nature of the bids and fluctuations in raw material prices and possibly the lack of risk management by some applicants, it could be rough seas ahead.

Sources tell StarBiz 7 that some smaller bidders under LSS5+ are even thinking of giving up their bids barely a month after winning them.

A key reason seems to be a recurrent theme in LSS projects – when bids were submitted prices of solar panels were low.

Now they are trending up.

“There is talk that some developers could withdraw from their concessions.

“It remains unclear whether such withdrawals would incur penalties or if the vacated allocations would be re-tendered to other bidders,” says an industry source.

Under LSS5+, the lowest bid is believed to be 13.75 sen per kilowatt-hour (kWh), industry sources tell StarBiz 7.

The range of tariffs in the two new LSS projects are between 13.75 sen to 18 sen per kWh. Tariffs in LSS4 projects ranged from 17.68 to 24.81 sen per kWh.

That begs the question – can you make a profit from such low tariffs?

The industry standard of assessing the viability of concessions, namely the internal rate of return (IRR), is key.

Industry players say that the IRRs for the new projects are ranging between 5% to 7%, which is very low and leave little room for cost overruns.

One problem is solar module prices, which are expected to increase by some 12% because of policy measures in China aimed at curbing excessive price competition.

Then there is the newly expanded sales and service tax (SST), which is being imposed on construction services.

“SST is kicking in after bids were submitted, so costs have risen unexpectedly,” says an industry player.

UOB Kay Hian Research estimates that project costs for LSS5 and LSS5+ could rise by up to 20%, reducing IRRs by one to 1.5 percentage points, to between 5% and 7%.

The research house also expects EPCC contractors to face margin compression of 1% to 2%, as the LSS project owners tighten budgets.

With the 4GW of capacity under LSS5 and LSS5+ being targeted for completion by 2027 and 2028 as per their concession terms, the industry is facing significant execution challenges, cautions Samaiden Group Bhd group managing director Datuk Chow Pui Hee.

EPCC player Samaiden listed on Bursa Malaysia five years ago and today trades at a price earnings ratio of 28 times, as investors seem to ascribe high value to such companies partly due to the country’s ramping up of its solar power ambitions.

“Delivering projects at this scale requires a much larger pool of subcontractors and skilled labour. Additionally, rising solar panel costs are adding further pressure on developers,” she tells StarBiz 7.

Financing has also become tougher, with banks closely scrutinising low-tariff projects with shorter deadlines, she notes.

“Compared to LSS5, LSS5+ faces greater challenges due to the tighter timelines,” she adds.

Samaiden, like other listed EPCC companies, has moved into owning solar farms under government programmes.

The company is in a consortium that was shortlisted to develop a 99.99 megawatts (MW) solar plant in Segamat, Johor under LSS5+.

This is the EPCC company’s second project as an asset owner, following its recent win for another 99.99MW plant in Pasir Mas, Kelantan under LSS5.

Chow notes that they need to ensure their financing rates for their projects are competitive as this will help their project IRRs.

“While many banks remain cautious, this has not been a major obstacle for us as we have the sukuk option as an alternative, apart from term loans,” Chow adds.

According to observers, some banks are increasingly hesitant to lend to LSS projects due to growing exposure to the sector – which includes Tenaga Nasional Bhd, the sole offtaker for all LSS initiatives.

That said, the ability to raise financing is correlated with a company’s financial standing and its track record in the sector.

And some like Samaiden are turning to the bond market.

Solarvest Holdings Bhd for example has established a RM1bil sukuk programme.

Under LSS5+, it is developing a 470MW solar farm in Perak’s Larut and Matang district through a 20:80 consortium with Malakoff Corp Bhd, which is one of the country’s traditional IPPs.

This is likely the single largest capacity award under LSS5+, point out analysts.

Notably, this is Malakoff’s debut in the LSS space, after failing in the previous LSS tenders, note analysts.

The group has been looking to grow its RE segment whose generating capacity only stands at 198MW currently.

Solarvest had earlier bagged the contracts to develop and operate a 60MW large-scale floating solar photovoltaic (PV) plant in Kuala Langat, Selangor, as part of LSS5.

It targets to achieve financial close for this project by the first half of next year, says group chief executive officer Datuk Davis Chong, noting that this should give the group sufficient time to commission the plant by end of 2027.

He adds while LSS5+ projects are challenging, his remains viable.

“The current tariff levels are increasingly separating serious, well-capitalised players from opportunistic entrants,” Chong quips. “Success now hinges on strong technical execution, disciplined cost management, and leveraging procurement scale to defend margins.”

Meanwhile, another first generation IPP, YTL Power International Bhd also won a bid in LSS5+, to build and run a 100MW plant in Kelantan.

Like Malakoff, YTL Power’s entry into LSS reflects a strategic pivot. Analysts point out these larger IPPs can afford to absorb early low returns in exchange for longer-term gains, such as building renewable capacity for future exports and offsetting their carbon emission profiles.

Another notable project under LSS5+ is a 200MW floating solar development on the Chereh Dam in Kuantan led by a consortium comprising Citaglobal Bhd and the United Arab Emirates’ Masdar, with a 51:49 equity split.

Masdar is a major global player in RE development and has projects in more than 40 countries.

The Kuantan project will be the largest of its kind in the region but with a floating solar development, its cost will be relatively higher.

The tariff awarded for this project is believed to be at a premium to other LSS5+ bids, given the complexity and capital outlay involved in deploying solar infrastructure over water.

Citaglobal’s executive director Aimi Aizal Nasharuddin estimates that an investment of RM800mil is needed and notes that this will be financed through a mix of debt and equity.

“As part of the bidding process, the consortium has already secured term sheets from financial institutions covering up to 80% of the project cost.

“The equity portion will be provided either through internal resources or via structured financing by the respective consortium members,” Aimi shares.

Citaglobal expects the project to deliver an IRR of 7% to 8%.

Meanwhile, a 51:49 consortium between Sunview Group Bhd (a public-listed EPCC player) and Cypark Resources Bhd was shortlisted to develop a 99.99MW solar PV, plant in Port Dickson, Negri Sembilan.

Cypark is confident in successfully and sustainably delivering LSS5+, drawing on valuable experience from LSS2 and LSS3.

Cypark’s plants from the latter two LSS programmes are now operational after overcoming several delays.

“Our experience with LSS2 and LSS3, among the largest in Malaysia, has been invaluable in strengthening Cypark’s capabilities as a LSS developer.

“We learnt the importance of rigorous project planning, disciplined procurement, early engagement with regulators, and partnering with proven technical experts,” its chief investment officer Belqaizi Taufik says.

“By applying these lessons, especially in driving cost efficiency and construction speed, we are confident of delivering LSS5+ on time and at the competitive tariff rates required.”

He concurs with other industry players that securing competitive funding is critical for LSS5+ success. To meet this challenge, he adds, Cypark has proactively positioned itself.

“All our concession assets are generating sustainable cash flows, and our comprehensive capital restructuring which includes refinancing of our borrowings with more competitive terms, has strengthened the balance sheet, unlocked capital, and reduced financing costs,” Belqaizi adds.

Weaknesses and solutions

While the LSS programmes created by the government and overseen and executed by the Suruhanjaya Tenaga have catapulted Malaysia’s RE journey, industry observers do note some weaknesses and proffer some suggestions.

Perhaps the most stark characteristic of the LSS projects is the emphasis placed on tariff bids, which some say could be leading to a “race to the bottom”.

Industry players say rather than price, more emphasis should be given to submissions that have higher levels of innovation.

“As a result of bidding based on tariff price, most players are focused on securing capacity awards though the low bids.

“But this is coming at the expense of exploring new technologies or value-added services that could enhance project viability and long-term returns,” points out one player.

Another issue relates to the moratorium imposed on winning bidders – there can only be a change of ownership of projects, five years after commercial operations begin.

The rationale for the rule is clear as the government does not want to encourage the winning parties to flip their projects for a quick buck. But the moratorium could be too tight.

First, it takes about a year to achieve financial close and at least another year to build the plant and even more time for commercial operations to begin.

Only then will the five-year moratorium begin.

For a company which has gained expertise in building new RE plants, it would only make sense to be allowed to divest some of its equity of the running plant to an investor drawn by the cash flows the plant is generating.

Those sale proceeds can then be deployed by the RE plant developer into their next project.

Hence, loosening the ownership moratorium should be something the authorities need to consider.