Testing year for Anwar and economy

THE year 2026 will be a decisive economic test for Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim.

The next election is in view and Malaysians are increasingly focused on income growth, cost of living and job security.

The parliamentary elections must be held by February 2028 but there are strong indications that the nation will go to the polls much earlier.

Anwar is already moving in that direction, judging from the Budget 2026 he tabled last October.

It was packed with welfare spending for households, incentives for businesses that were complaining about margin compressions, and at the same time, avoided new taxes.

Now, Anwar must prove to voters that his administration can drive more reforms and keep the economic growth intact as export momentum cools and investment becomes more selective.

Meanwhile, the external backdrop remains complicated.

Global macroeconomic uncertainty persists despite some clarity on US import tariffs.

For a trade reliant economy like Malaysia, that is a material risk.

Most economists, however, do not expect a sharp downturn in 2026.

Growth is likely to moderate from 2025 but remain close to the country’s estimated potential.

Private consumption should remain the main anchor, supported by income measures, a still firm labour market, ongoing investment flows and the prospect of easing monetary conditions.

Tourism is set to provide an additional buffer with Visit Malaysia Year 2026. The government’s ambitious aim is to attract 47 million tourist arrivals and generate RM329bil in tourism revenue.

This would provide a further boost to the already strengthening ringgit, which in turn would help temper imported cost pressures and support confidence.

A better run in equities, supported by returning global funds, would also strengthen sentiment and indirectly reinforce the administration’s economic credibility.

Looking into 2026, economist Geoffrey Williams expects the positive momentum from 2025 to carry over.

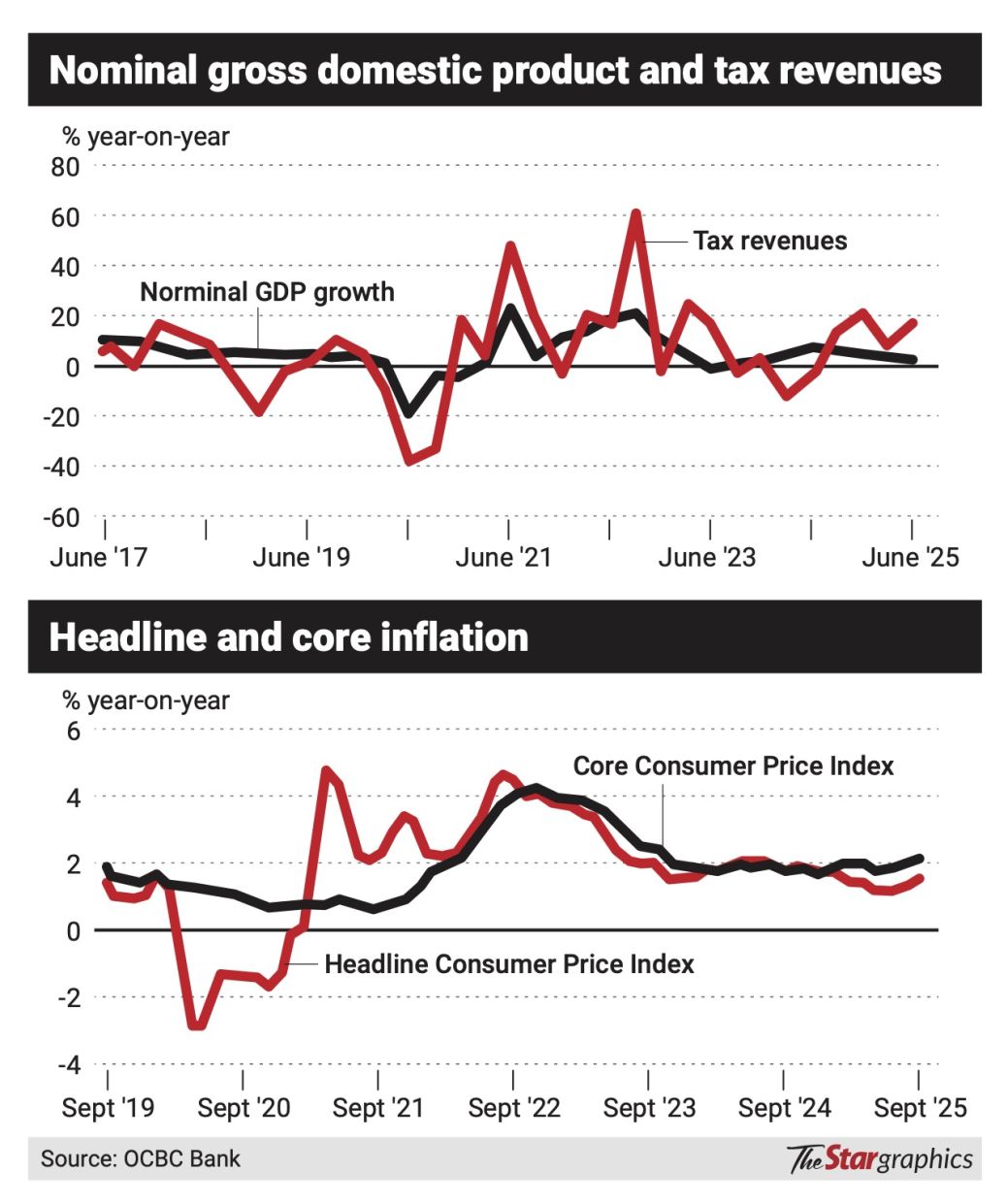

“Economic growth is likely to be around 4.7% in 2025, which is in line with underlying potential and forecasts.

“Inflation is low, around 1.3% to 1.5% at the lower end of the forecasts. The ringgit is strong and other indicators are also good.

“This is a firm foundation for 2026 and we should expect a similarly strong performance next year,” he tells StarBiz 7.

Williams, however, stressed that the outcome still depends on external developments and domestic political factors.

At this point, it appears that Malaysia’s trade with the world is likely to stabilise, especially since the tariff issues with the United States are over.

“If the government reopens the US-Malaysia Agreement on Reciprocal Trade, it would be a mistake,” according to Williams.

Lee Heng Guie, executive director of the Socio-Economic Research Centre, foresees Malaysia recording a real gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 4.5% this year, only marginally lower than 4.7% in 2025.

“We pinpoint the supportive income policies (such as cash handouts and civil servants’ salary increment), ongoing investment catalysts as well as less restrictive monetary policy to anchor domestic demand.”

Not everyone is as confident on the near-term cycle.

OCBC senior Asean economist Lavanya Venkateswaran sees a clearer slowdown, driven by a payback in trade flows and moderation in investment.

“We see cyclically slower GDP growth of 3.8% in 2026 due to reduced exports to the United States, weaker external demand and some moderation in investment spending,” she says.

Lavanya’s assessment highlights the fact that 2025’s growth was flattered by temporary export timing, and that 2026 will be more reflective of demand conditions. The most consistent support for growth is still private consumption.

Lee expects household spending to remain firm, helped by income measures and labour market stability.

That resilience matters because it is the buffer when the external sector softens.

It also matters politically, since consumer sentiment can shift quickly when essentials feel expensive even if headline inflation looks low.

Universiti Malaya’s Distinguished Professor of Economics Rajah Rasiah puts cost of living pressure and food vulnerability at the centre of the household story.

“Unless Malaysia’s farmers, especially small farmers, embrace Industrial Revolution 4.0 instruments aggressively to raise food productivity, Malaysia will remain a net importer of food, which will prove costly for the average Malaysian.

“The government must strengthen its focus on food security.”

This matters because food inflation does not need to surge to become a political and economic drag. Even a small spike can make a big difference.

Rajah highlights that monthly food inflation rose to 1.5% in November from 1.4% in October 2025, and argues food security is a policy priority, not simply a social concern.

His view is that wage policies can keep retail demand supported, but food import dependence can erode real purchasing power if productivity gains do not materialise, especially among small farmers.

Rajah also notes that the World Bank has upgraded Malaysia into high income status last month, and argues it is partly linked to currency appreciation, which should be treated carefully given Malaysia’s heavy reliance on trade.

The ringgit becomes relevant as well, since currency swings affect imported cost dynamics and confidence.

Williams sees no specific base case risk to inflation or growth, but warns about the possibility of currency adjustment after a strong year.

“The current level is likely too high and the market will correct that, the question is whether it will be a sharp correction or a gradual realignment.”

Another key risk is external sector dynamics.

Malaysia remains highly open, and even modest shifts in global demand can move export volumes, earnings, hiring plans, and capital expenditure decisions.

Lee lists several channels of downside risk, including the prospect of slower global growth due to general or sectoral tariffs, financial volatility linked to a sharp correction in artificial intelligence-related equities, and delays in public project spending or disbursement.

His warning is straightforward and relevant.

“A policy misstep can significantly increase market uncertainty and volatility, prompting businesses and consumers to delay investment and spending decisions.”

Lavanya’s work provides a more detailed map of the trade cycle risk, especially in relation to the United States.

She argues that export performance in 2025 was distorted by frontloading, with export growth to the United States swinging widely through the year.

She estimates that the monthly value of exports to the United States averaged RM18.5bil for the first three quarters of 2025, compared with RM15.6bil in 2024 and RM13.3bil in 2023, suggesting frontloading of close to RM2.8bil a month.

As exemptions expand, she expects less need to frontload in 2026 and sees export growth to the United States turning negative next year.

Her biggest concern is the possibility of sector specific semiconductor tariffs.

She estimates that electrical and electronics appliances accounted for 60.2% of exports to the United States in the first half of 2025.

She warns that under a more adverse tariff scenario, GDP growth could be lower by around 0.4 percentage points.

Even without new tariffs, she expects the global semiconductor upcycle to continue at a slower pace, citing the World Semiconductor Trade Statistics projection that global shipments will ease in 2026 versus 2025.

Rajah, on the other hand, says it is difficult to predict how much exports will slow in 2026, especially since uncertainty itself has already affected businesses, with the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers reporting chaos and uncertainty in trade, especially for small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

He also argues Malaysia may not face a severe contraction because much of its electronics exports are produced by American firms in Malaysia for the United States market.

That may cushion aggregate export outcomes, but it does not remove the domestic challenge of ensuring local firms and workers capture more value from the export and investment ecosystem.

That brings the discussion to investment and spillovers, where the difference between headline approvals and actual economic outcomes can widen.

Williams points to foreign investment momentum supported by data centres and construction related activity in initiatives such as the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone.

He expects those projects to continue in 2026, but he stresses that domestic income benefits require deliberate value capture.

His concern is that a portion of the value can be repatriated, making domestic spillovers harder.

Lavanya expects investment spending to stay resilient but moderate.

She argues that large import bills can be staggered, which would help keep trade and current account balances comfortable even as exports slow.

She also highlights that capital goods imports are closely linked to machinery and equipment investment, which accounted for 41% of gross fixed capital formation in the first half of 2025.

Lavanya expects machinery and equipment investment to slow alongside a moderation in capital goods imports, and anticipates structural investment to cool as construction growth normalises.

She also flags pipeline challenges for SMEs in 2026, from the final phases of electronic invoicing to higher utilities and indirect tax related cost pressures.

She also points to labour market policy shifts that can raise operating costs, including mandatory Employees Provident Fund contributions for non-Malaysian employees starting Oct 1, 2025 and a multi-tier levy mechanism implemented from 2026 to reduce reliance on foreign workers.

Her survey reference is a useful indicator of how thin buffers can be.

The Samenta Ipsos SME Outlook Survey 2025 and 2026 released in September 2025 showed that 69% of SMEs planned to raise prices to deal with higher input costs, while 70% had less than six months of cash reserves.

Even when demand is not collapsing, limited cash buffers can force firms to delay expansion, reduce discretionary investment, and tighten hiring.

Thus, it was not surprising that World Bank lead economist for Malaysia Apurva Sanghi foresees a “restrained” 2026.

In October, Apurva noted that business confidence indicators have been trending downwards, which can lead firms to hold off on capital expenditure.

Against such a backdrop, the International Monetary Fund’s recent statement on Malaysia highlighted the critical need to rebuild Malaysia’s macroeconomic buffers.

The Washington DC-based fund projects Malaysia’s GDP growth slowing marginally from 4.6% in 2025 to 4.3% in 2026.

Looking ahead, execution matters more in 2026 than it did in 2025 because the margin for error narrows when growth is moderating.

Lee’s point about implementation risk is critical in an election sensitive period, since delays in spending and unclear sequencing can prompt firms and consumers to postpone decisions.

Williams also frames 2026 as a year where outcomes depend on domestic political factors as well as external ones, which is another way of saying that confidence and credibility will be tested.