Mission heavy, not impossible

IT is not easy to describe the role of Khazanah Nasional Bhd. To its detractors, the sovereign wealth fund, which has been around since 1993, has a blurred focus.

It has sought to straddle its role as an investment company tasked with delivering financial returns to the government while also playing a nation-building role.

But are the two pursuits compatible?

For managing director Datuk Amirul Feisal Wan Zahir, the dual mandate has been there from day one, but along the way, the balancing act got challenging.

“When I assumed this role in July 2021, I walked into a period of significant stakeholder uncertainty and shifting leadership, made harder by Covid-era constraints. That ambiguity forced a fundamental reset.

“I went back to Khazanah’s original purpose, that it has always carried a dual mandate,” he says.

He adds that the organisation had drifted into an “either-or” debate between pure intergenerational wealth-building and developmental responsibilities.

Amirul Feisal then changed a structure that Khazanah used to have, which was separate commercial and development investment funds.

Instead, every investment is looked at from financial returns as well as how those investments can have a positive impact on Malaysia’s business landscape.

Case in point: when Khazanah invested in California-based artificial intelligence (AI) firm Syntiant Corp in late 2024, the idea was that Syntiant would establish a research and development centre in Malaysia.

Syntiant also used the investment proceeds to buy a consumer micro electromechanical systems business in Penang, which already had significant assembly and testing operations.

“All of this will contribute to Malaysia’s ambition to move up the semiconductor value chain,” enthuses Amirul Feisal.

Financial returns remain a key focus, on the basis that one feeds into the other – without the financial returns, how then would Khazanah be able to embark on its development investing roles?

One example of the latter is Khazanah’s Dana Impak programme, with RM6bil committed to invest in semiconductor and advanced manufacturing, mid-tier companies and start-ups.

These investments are being made mainly through investment in other funds, which not only diversifies risk but also boosts the local venture capital and private equity sectors.Coming back to its financial returns, it’s difficult to find fault in Khazanah’s performance. Its investment portfolio returned 5.2% in terms of net asset values (NAV) in 2025. (Investment funds gauge their performances by NAV, which is a reflection of the actual market value of the underlying assets per share, after deducting liabilities.)

Khazanah’s annual returns were 6.1% for a seven-year rolling period.

In comparison, Singapore’s Government Investment Corp (GIC) (which does not disclose a simple one-year NAV growth number publicly) achieved only a 3.8% annualised real returns over 20 years ended March 31, 2025.

Temasek, meanwhile, reported a 10-year total shareholder return of 5% for the year ended March 31, 2025, while Norway’s Norges hit a spectacular return of 15.1% last year.

However, comparing the performances of sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) can be tricky. They have different asset sizes – GIC has total assets of US$800bil and Norges a massive US$1.9 trillion.

The SWFs also have varying roles. GIC and Norges invest outside their home country markets and mainly for financial returns while Temasek has a developmental role similar to Khazanah.

In Khazanah’s case, its investments in global public markets have been key.

While only accounting for about 20% of its total assets, global public markets achieved an 11.7% return in 2025, which would have been more than double if not for the ringgit’s sharp appreciation.

Khazanah invests in global markets using top investment managers abroad as well as through instruments such as exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Sources say top stocks like Nvidia Corp account for some of the biggest gains for Khazanah, which does not reveal its actual global holdings.

Finance associate professor Dr Liew Chee Yoong of UCSI University Malaysia notes: “In recent years, Khazanah has demonstrated portfolio resilience, improved diversification and competitive returns relative to its size. This suggests stronger capital stewardship and a more adaptive asset allocation strategy, particularly in navigating post-pandemic global volatility.”

But what about its local holdings? Khazanah is best known locally for its major holdings in some of the country’s top government-linked companies (GLCs), namely IHH Healthcare Bhd, CIMB Group Holdings Bhd, Telekom Malaysia Bhd, Tenaga Nasional Bhd, Axiata Group Bhd, Malaysia Airports Holdings Bhd (MAHB), Malaysia Airlines Bhd and PLUS Malaysia Bhd.

In fact, the main “investment” that the government of Malaysia had seeded Khazanah with since its inception has been the transfer of such assets into Khazanah.

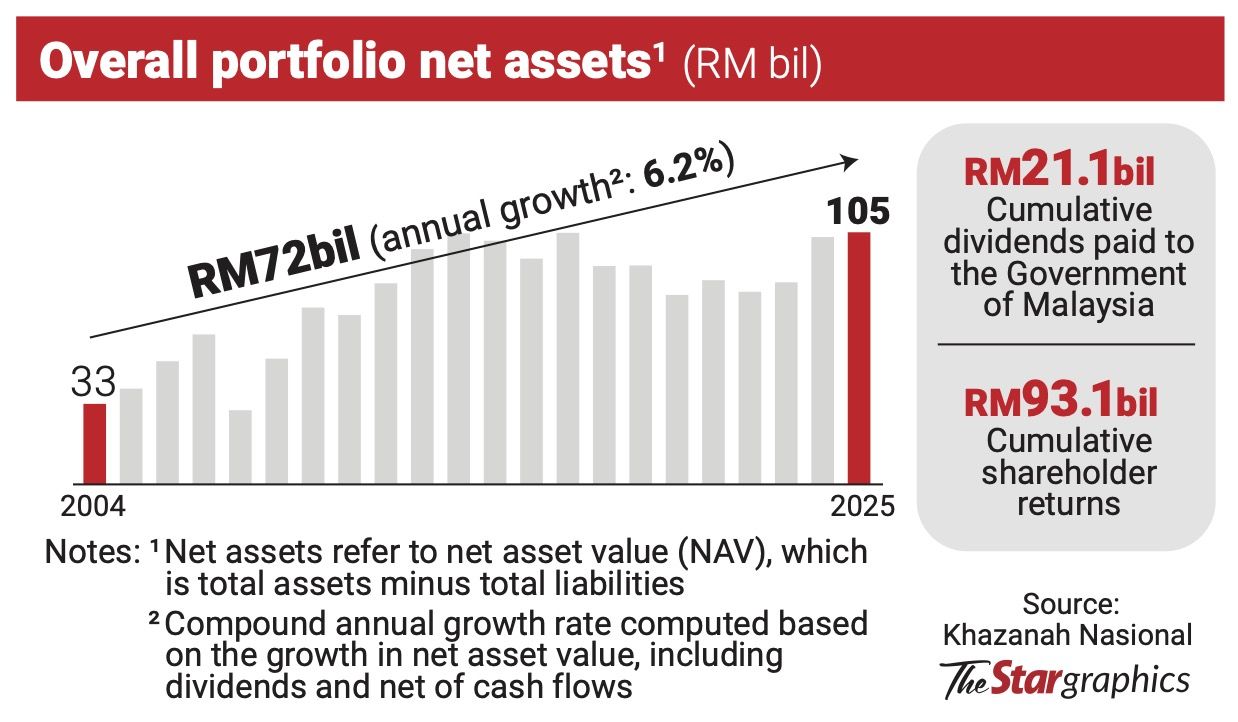

Khazanah’s role was to revitalise and monetise these assets. Today, Khazanah has total assets worth RM156bil and has returned cumulatively RM21.1bil in cash dividends to the government.

From 2005 to 2015, Khazanah embarked on a GLC transformation programme that reshaped how these companies were run. The idea was to turn these politically-linked and underperforming firms into commercially driven, competitive companies.

Khazanah today is looking to push that agenda, with an even bigger picture. One key investment tenet is to enhance “connectivity” in the country.

A key move by Amirul Feisal’s team was the privatisation of MAHB, which was completed early last year. The exercise was to enable MAHB, which had been underperforming, to act faster and invest more boldly into its ageing assets.

Investors such as Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP) and Abu Dhabi Investment Authority were brought in.

GIP is an infrastructure fund with a track record in managing and improving airport assets globally.

Despite facing some criticism that Malaysia’s top airports are yet to see any significant improvements, Amirul Feisal points out that there has been a 11.2% increase in passenger traffic since last year, supported by 15 new airlines into Malaysia.

Tied to the connectivity theme are ongoing improvements in Malaysia Airlines and the refurbishment of national heritage buildings such as Seri Negara and the Bangunan Sultan Abdul Samad Complex.

But what is a SWF doing restoring old buildings? Surely that should be the job of another government agency?

For Amirul Feisal though, every project Khazanah ultimately takes on, has to have commercial viability.

“The connectivity cluster is about ensuring that our airline, airport and tourism assets create a multiplier effect for the economy. Our refurbishment efforts on the heritage buildings have to be financially sustainable.

“With capital and institutional support in place, the area opened up. Before long, we start to see vibrancy. People can live, play, and stay longer. Importantly, it is already financially sustainable – and that has always been the goal.

“As a result, we need to buy more planes with rising airport traffic. This benefits the airlines, highways, telecommunications and power segments. The multiplier effect across the economy is significant,” he says.

Perception issues

Despite all this, Khazanah continues to have its fair share of detractors.

Economist Geoffrey Williams says Khazanah’s total assets of RM156bil is “very small compared to any comparable SWF and far too low to be fit-for-purpose”.

Williams also points out that Khazanah’s 5.2% return last year and its seven-year rolling annualised return of 6.1% is poor.

“If it had invested in a simple ETF on the S&P 500 it could have delivered 14.4% over the last year or 77.2% over the last five years.

“The returns to the government are very small: RM2bil from total assets of RM156bil last year only yields 1.28%. It would be better to put it in a fixed deposit,” he says.

Indeed, Khazanah is often the target of potshots about bad investments in the past.

Like every investment fund, some bets turn sour. And due to Khazanah’s high profile, it has received brickbats as a result of its investments in KidZania, Blue Archipelago Bhd, FashionValet and Iskandar Malaysia Studios.

Increasingly, more is being expected from Khazanah, in terms of how it goes about its investment decisions and information on its exact investments.

Adds Liew: “From a governance perspective, expectations have increased. As a custodian of national wealth, Khazanah is judged not only by financial metrics but also by transparency, accountability, and its contribution to broader economic transformation. Public scrutiny and parliamentary oversight reflect the importance of its role.”

In response to this, Amirul Feisal says, “We acknowledge that in our mandate to steward national assets and grow Malaysia’s long-term wealth, risk is the unavoidable price of return. To demand a portfolio with zero impairments is to demand a portfolio with zero innovation.

“If we never failed in a venture investment, it would imply we were not taking the necessary risks to spur national development. Our focus is on the aggregate performance, growing net asset values from RM33bil in 2004 to RM105bil today, allowing us to build a resilient, diversified portfolio that serves the nation.

“Criticisms often focus on isolated transactional losses, viewing them in a vacuum. However, our accountability must be measured by the resilience of the entire portfolio.

“Since 2004, we have delivered a robust compounded annual growth rate and cumulative dividends of RM21.1bil to the government.

“This ‘portfolio approach’ ensures that we grow Malaysia’s long-term wealth by balancing high-growth, high-risk assets with stable, income-generating ones, ensuring that the rakyat’s capital is protected in the aggregate, even when individual bets do not pay off.”

Indeed, not all SWFs are bereft of bad deals.

During the global financial crisis, GIC bought a large stake in Swiss bank UBS. The investment lost about 70 % of its value as markets fell and UBS needed capital injections.

GIC also lost money on the US property bubble, while Temasek invested in crypto exchange FTX before it collapsed in late 2022. After FTX’s bankruptcy amid fraud allegations, Temasek wrote off its entire US$275mil.

Big bets on tech and mid-tier companies

Going forward, one of the bigger bets that Amirul Feisal is taking must be the money being spent under Dana Impak. But how then would its success be gauged?

Amirul Feisal says it is no longer just about generating commercial returns, but about the “multiplier effect.”

“For example, through Jelawang Capital’s emerging fund managers’ programme, we have already seen our commitments catalyse over RM30mil from other investors.

“We must be honest about where we fall short: while we have improved in market reach and talent, we lag in exits. This is where Dana Impak is critical.

“By catalysing the VC ecosystem (through Jelawang Capital) and levelling up Malaysian mid-tier companies, we are not just crowding in capital; we are structurally aiming to support firms throughout their lifecycle”.

Amirul Feisal says that this will take time – between three and five years. “A successful ecosystem is when there are more exits,” he says.